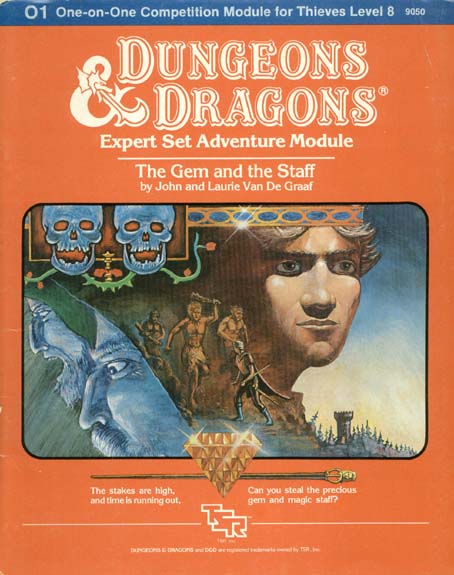

On Tuesday nights, Dan and I are exploring one-on-one D&D play. We started with cooperative playing some of the solo modules, and then recently have started in on the first module written for one DM and one player: O1: The Gem and the Staff. Something about this module hasn’t sat right with me, but I can’t just say it’s bad design, that’s bad critique. So I found myself trying to figure out exactly what my gripe with this module is.

So far we’ve played the first half of the module, “the gem part” as Dan says, over the course of two sessions. You can watch them here and here if you like. Note that after this spoilers abound, so if you want to watch the videos and/or read the module, please do so before proceeding.

Let me start my critique by saying that Dan is an excellent DM, and I very much appreciate him running this module for me. It has been really fun, and I look forward to playing the second half. Honestly, this is why I find my reaction to certain parts confusing – the module has a lot going for it, and when I got into it I really got into it. I love the premise of playing as a single thief doing a break-and-enter job on a powerful wizard’s tower. So where did it irritate me?

The first obvious irritation comes at the end of the first session, when I get trapped in the Amazing Art room. At this point I’ve been talking to a magic statue which has given me some odd riddles, which I have not yet figured out. I did not realize that it was announcing the name of the room as I entered, and had I allowed myself to break immersion and think as a 1983 era game designer for a moment, I probably would have realized the inherent pun and turned away.

At the start of the next session Dan narrated me out of that room, and then I used the statue announcements to my advantage, using its clues to pick which door to explore next. The next room was quite enjoyable, and I felt like I was back in the shoes of a fantasy thief breaking into a wizard’s tower. I was pleased to not fall for the obvious honey-pot, and to intuit the location of a secret door at the back of the wardrobe. Both felt very much like the kind of things a powerful wizard might have in his personal chambers.

But then as I approached the next door there was the magic voice again giving me clues about the room I was about to enter. My head was back in puzzle solving space, though I tried my best to roleplay a thief attempting to outwit the fey folk guardians in the wizard’s garden. The voice again announced the next room, which turned out to be the wizard’s personal study, though there was no evidence of any wizard present. Given the lack of wizard, the clue still buzzing in my head, and some of the elements in the room (the windows, the color-coded alcoves) my head was immediately back in puzzle solving mode. So it’s not surprising that I stumbled right into the invisible wizard and got my ass handed to me.

This last room is actually my second point of frustration. In retrospect, I feel like some really cool stuff could have happened in this room. But because I wasn’t paying attention or in the right mindset, I stopped playing the sneaky thief and was just trying to second guess the designers to solve the next riddle and progress. I should have taken more care moving about the room. I should have been moving silently. Why didn’t I do these things?

Ultimately, I blame that disembodied voice. Announcing a clue before I enter each room just completely broke any immersion I was feeling. It reminds me of an old Mel Brooks interview I once saw, when he was describing the difference between his directorial style and that of Gene Wilder. Gene, he says, never wanted to break the fourth wall, while Mel likes to occasionally wink at the audience.

Personally, I’m with Gene on this one. I want to keep my head grounded in pretending to be a thief in a wizard’s castle, and let that guide my actions. Unfortunately there are a lot of design elements in this dungeon that just make no sense at all, even for a mad wizard. The worst of these, frankly, is the disembodied voice announcing clues about what’s behind each door as you approach it. I know which door in my house leads to the bathroom, and where the safe with my passport in it is hidden, and I don’t leave clever clues around the house about it.

I much prefer the Gygaxain B&E of the G series to this quirky series of puzzles by the Van De Graafs. Sneaking into the Hall of the Fire Giant we’re presented with a lair that actually makes sense for a tribe of fire giants. Here in O1 we have the tower of a mad wizard, whose madness is perhaps most underlined by the utter implausibility of the layout.

Actually, a lot can be forgiven regarding some of the weirder elements found in the tower. Would a crazy wizard have a weird art-gallery with no artwork that can only be traversed in a single direction? Maybe. I like the notion that it was actually still in the works, though I’m not sure if that was a Dan Collins flourish or in the original text. Might he have a passage with a retracting bridge and an invisible door? I mean, that seems pretty inconvenient, but maybe he’s got boots of levitation or something so it’s not a big deal for him? But I just can’t come up with any logical explanation for the magic voice. It’s literally the voice of the authors, telling me they made some of the puzzles a bit too hard, so they’ve attempted to balance it with clues that they’re just going to spoon feed to me as I go from room to room.

I don’t think it’s unfixable though. Honestly, I’d be inclined to just give it a little more personality. What if instead of a strange disembodied voice, there was a little demon who actually meets and speaks to the player? Perhaps a minor imp the wizard has summoned to do light house work and despises its lot in life. It wishes the wizard ill, but cannot directly interfere due to the bindings of the spell, so it finds silly ways to deliver hints to the player in hopes that maybe the player might stumble into killing its master.

Also, were it me, I would try to make the interior layout of the tower actually make physical sense. It’s a minor detail, but the total disregard to physics just to present the player with a series of clever puzzle rooms is also a tad fourth wall breaking for me. I know, he’s a mad wizard, etc. But every mad wizard does not necessarily have to live in a building designed by M. C. Escher.

Huh, interesting.

I am completely unfamiliar with this module (though I’ve heard Dan mention it in the podcast before), so I can’t speak to the design issues from any sort of “experience.”

There are certainly a lot of challenges involved with running a solo adventure. While encounters can be scaled to the single PC, we tend to forget the way multiple heads/personalities can come together with ideas that help overcome or mitigate challenges in an adventure. One does not have to “on point” (in the adventuring mind set) at all times when you have comrades to help pick up the slack. It takes a certain type of player to do hard core solo adventuring, even in a fairly whimsical dungeon like the one you describe. I imagine that for many players it would be very (mentally) fatiguing.

I guess I’m suggesting that even if the helpful hints were staged better (with a friendly demon or whatever), you still might not like the play of the game. Instead of being irritated with the weirdness of the mouths, you might feel weird about teaming up with an NPC (in effect, teaming with the DM) against the DM/NPCs.

I’d guess it would simply result in an unsatisfactory game play. D&D seems to work best in cooperation with others.

I’ll second the comment that having 2+ minds on the players’ side makes a big difference in the degree of challenge and add that having multiple PCs also increases the margin for error. With 2+ PCs, having one run out of hit points or fail a save-or-die roll escalates the tension. With only 1 PC, it brings a hard stop to the game, unless the GM is ready and willing to handle multiple degrees of failure.

On having a staged helper, there was a DCC module from one of their Free RPG Day releases (Elzemon and the Blood-Drinking Box) that involved an imp that wants to do the minimum to harass PCs breaking into its owner’s tower because their success would free it from bondage. I haven’t run it yet, though I’ve earmarked as sounding like a pretty fun time, but I don’t think it’d be hard to adapt it for use with a solo PC.

On which note, I disagree partially that D&D works best in cooperation with others. If you run it the same way that you would for 3+ players, yes, you’ve leaving out a lot. However, that’s like playing baseball and complaining that it’s not as fun with only 1 player per side. It’s perfectly possible to play DM+1 in a way that’s as much or more fun than playing in a group. A friend and I are having a great time running a DM+1 campaign through weekly 30-60 minute Whatsapp calls, and that hasn’t been an outlier experience for me (just during the pandemic, I’ve had players tackle Death Frost Doom and Tower of the Stargazer solo). There’s also this recent video from Matt Colville where he says every player he’s run through a DM+1 game said it was the most fun D&D they’ve played, so it’s not just my experience. It takes some differences in approach, but it’s perfectly viable.

I actually just started on a series of blog posts about how to run D&D to suit DM+1 play, though I haven’t yet gotten further than the intro. I’m aiming to get the post on scope up today and to get at least 2 more posts per week up going forward, so I should have that all posted by the end of the month.

The magical voice is actually a bored invisible stalker. If you get the medallion of seeing invisibility from the troll in the room that you didn’t explore, you can see him. There’s also one last screwjob at the end that you didn’t get a chance to see or fall for.

That is really fascinating. It’s just too bad the text doesn’t bring this to the forefront ever. It’s kind of similar to players who make brooding characters with a dark secret – if you don’t actively work towards subverting your character’s desires and get that secret out, nobody will ever appreciate it and it might as well not have existed. In this case, it just comes across as a ham-fisted way for the authors to deliver clues.